LIFESTYLE | The unbearable lightness of fashion

The unbearable lightness of fashion

Words have a life of their own, their own colour and breadth. At times, when abused or distorted, they lose their value. This is precisely what has happened with ‘sustainability’, a word whose meaning is, at its origin, entirely noble.

Pity that, as time went on, it has been so often written and pronounced in the world of excess which we live in, that it has become tattered and frayed.

By Renata Mohlo

To believe that the word ‘sustainability’ is, by now, the most repeated term in marketing, where it has replaced the likes of ‘dynamism’ and ‘quality’. A wave of greenwashing has drenched just about every manufacturing sector, including the oil industry. The hypocrisy is tacit and tolerated. Some time ago, I was thinking about this very thing with Carlo Petrini, the founder of Slow Food. As he put it: ‘The word is quite clear, but we Italians, from an etymological point of view, have been the worst at interpreting it. If you ask 100 Italians what sustainability is, they’ll tell you that it’s something that permits a different approach to production, etc. Our French friends are right to translate it as durable, and we Italians are wrong in thinking that sostenibile is something that, all considered, doesn’t destroy the environment. Durability, the ability to hold up over time, means that any act I complete must be done in such a way so that even future generations can enjoy its fruits. Conversely, our attitude up until now has been something else. It’s selfish to think that resources are infinite,that they can be grabbed hand over fist’. Petrini concluded: ‘But we’ve reached the point that the finitude of things is forcing us into a paradigm shift. If we don’t change the paradigm, sustainability is truly empty and devoid of meaning’.

There’s no denying that we have a giant problem, which should shift our focus to discussions about the entire capitalist system and the inability to control the collateral effects of globalisation. A problem based on the desire, on the will to imagine communication strategies that only look to persuade and induce purchases. To infuse a sense of inadequacy which forces us to always want more: the t-shirt we don’t have (yet), the overcoat in the colour we saw in the advert. The fashion industry, which is a substantial part of the Italian economy, plays an important role in this dynamic.

Over the last twenty years, fashion has twisted in upon itself. There are always more events and they’re ever closer together. The obsession with novelty leads to the creation of a skewed, frenetically accelerated timeline. Any brand which aspires to international markets must consider an infinite quantity of variables. Not just taste which, despite becoming flatter and less varied, is still determined by different cultural factors, all while having to respond to distant latitudes and geographies. Geopolitics, which is increasingly unpredictable and fluid, confuses ideas and substance. Everyone is simultaneously talking to everyone: to consumers with infinitely diverse needs.

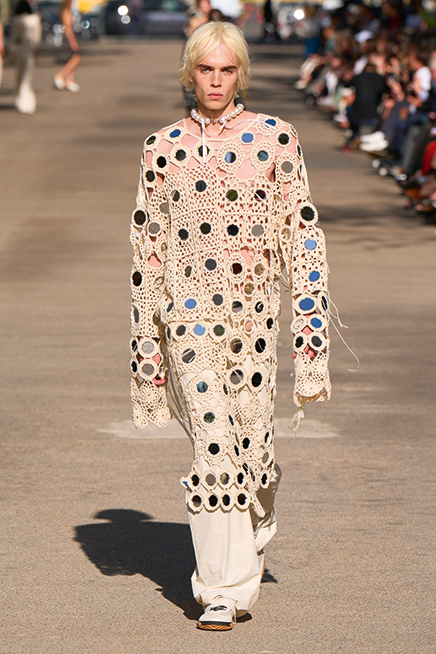

Moreover, an explosion of the ‘fast fashion’ market, ‘disposable’ fashion, which is cheap and trendy but extremely polluting, has caused irreversible damage. It was born to offer the less well-to-do segments of the world population the illusion of sharing a certain aesthetic with phony idols, celebrities and influencers. The scented wake of ready-to-wear luxury is offered to them, that which they see on social media or in the very few shiny magazines that still exist. It’s a powerful phenomenon.

These clothes are produced by giants like H&M, Zara, and Shein with low-quality fabric, in places like China, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Vietnam, where labour costs very little and people work unsustainable hours and in rather unsafe conditions.

It’s hard to monitor the manufacturing supply chain, which is long and nebulous. An infinite production of rags which reaches the United States, Europe and Asia, where they’re sold at low prices to be worn just a few times. In Europe alone, two million tonnes of textile products are thrown away every year. According to Oxfam, 70% of garments are shipped to Africa, where they’re sold in local markets.

Used clothes, which come from as far as the US and Japan, are an opportunity and a convenient solution, though they also give rise to a series of serious environmental and economic problems. The first is the disposal of unsold and un-sellable items.

It’s impossible to know with any precision what the negative environmental impact is.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the fashion industry is responsible for the production of about 10% of all carbon dioxide globally and of a fifth of the 300 million tonnes of plastic produced each year. Even natural materials, like cotton, have a massive environmental footprint: according to the WWF, it takes 2,700 litres of water to produce the cotton used to make just one t-shirt. And that doesn’t consider the widespread application of pesticides and fertilisers at factory farms. Sure, there’s organic cotton, made with very little water and without toxic chemicals, but it currently makes up just 1% of global production.

In this light, one alternative solution to fashion’s pollution problem is the next-gen material industry. These materials are made by fermenting and growing bio-based substitutes for materials of animal origin (such as leather) and for synthetic materials made from fossil fuels (such as polyester). Some of these new bio-based textile products can be designed to have specific performance qualities, along with properties such as biodegradability. Since day one, Stella McCartney has used these innovative materials for her collections: from vegan leather (‘animal & cruelty free’), to recycled nylon and polyester, up to Bananatex or fabric made from seaweed. For her SS 2024 collection, McCartney has assured us that 95% of the materials used are ‘eco-conscious’.

In general, the adoption of sustainable practices is a challenge. However, this doesn’t mean that the industry isn’t open to change. Quite the contrary. In the past few years, the fashion industry has become more aware and has started to tackle the problem. According to the sustainability report by Launchmetrics, Making Sense of Sustainability, published in partnership with the Camera Nazionale della Moda Italiana (National Chamber for Italian Fashion) in the first quarter of 2022, fashion generated an MIV (Media Impact Value, an algorithm-calculated metric) of 618 million dollars: the fashion industry made up one third of all conversations about sustainability. Words. In this regard, the Fashion Pact, created in 2019 at the G7 to call for a radical change in fashion's approach to the environment, has been signed onto by over 200 brands (including Chanel, Zegna, Ferragamo, the Armani Group, the Kering Group, and Prada) which represent all price segments and about one third of the fashion industry. But for now, all we’ve seen are widespread debate and optimistic roadmaps. Nothing but greenwishing, with sporadic concrete results.

A few years ago, in an interview, Carlo Capasa, Chairman of the Camera della Moda Italiana, proudly told me about the Green Carpet, the first of its kind. Founded in 2017, this international event is all about sustainability in fashion: it stars the world’s most prestigious and virtuous brands and brings big-name performing artists who are sensitive to the theme to the stage, for a dash of Hollywood in Milan.

For the 2023 edition, Gucci received the Ellen MacArthur Foundation Award for Circular Economy for its Denim Project, which aims to combine regeneratively grown cotton and post-consumer recycled fibres which have been recycled, collected and re-spun in Italy, using them to make the collection’s garments. Moreover, a digital passport was introduced which will make it possible to verify the path a raw material has taken before being turned into a finished product.

In this regard, the Camera della Moda has been busy creating a ‘guaranteed chain’, or rather a blockchain, which certifies the various phases of production, ‘to obtain the complete traceability of a garment, just as happens with food’, explained Capasa. But this process, which is already challenging for very costly items, is unimaginable for garments with bargain-barrel prices: ‘Fast fashion plays by different rules’.

‘Completely sustainable fashion may be a utopia, yet sustainability is a utopia that we must live with and fight for’, Giorgio Armani recently stated. ‘We owe it to ourselves, to the planet, and above all to the generations to come. It’s a commitment we have to constantly measure up to. Today we are aware that corporate profits can no longer be the only goal’. An affectionate and admiring mention goes to Vivienne Westwood, a forerunner and pioneer that everyone, truly everyone, owes a lot in terms of inspiration. She was a convinced environmental activist well before anyone else. The motto ‘Buy less, choose well, make it last’ is hers, after all. We’re still far off, but between optimistic utopia and cynical realism, the issue is clear.