EYE ON ART | Interlocking poetry

Interlocking poetry

He was awarded top honours at the 1964 Venice Biennale in the sculpture category and was the Director of the Accademia di Brera. He’s one of Italy’s most renowned twentieth-century sculptors, beloved and appreciated by collectors around the world. A diviner of stone, an admirer of the balance and harmony of classical art, and a friend of enlightened architects and businesspeople, from Gregotti to Zanuso, from Aulenti to Gardella. His work has enriched legendary places, such as the Olivetti boutiques in Düsseldorf and Buenos Aires, and places of worship, such as the Church of San Lorenzo in Porto Rotondo, Sardinia.

By Cristiana Colli

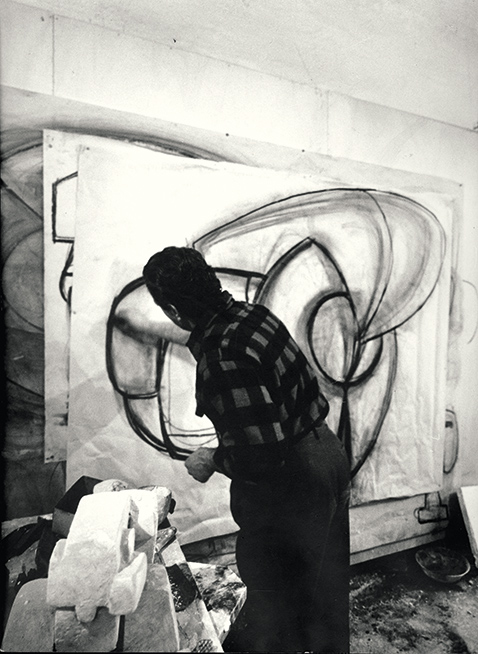

There’s an image of Andrea Cascella in his studio in Milan, taken over the shoulder, charcoal in hand, which captures him in the energetic, decisive act of etching lines which are already volumes. That photograph encapsulates a whole, complete understanding of design which contains the spatiality of stone, and you feel the power of the material as it reveals itself. Cascella was born a figurative artist, but he soon heeded the call of the seductions and interrogations of abstract forms: in part influenced by artists such as Brancusi, he came to a synthesis around the fundamental elements of geometry in his mature years.

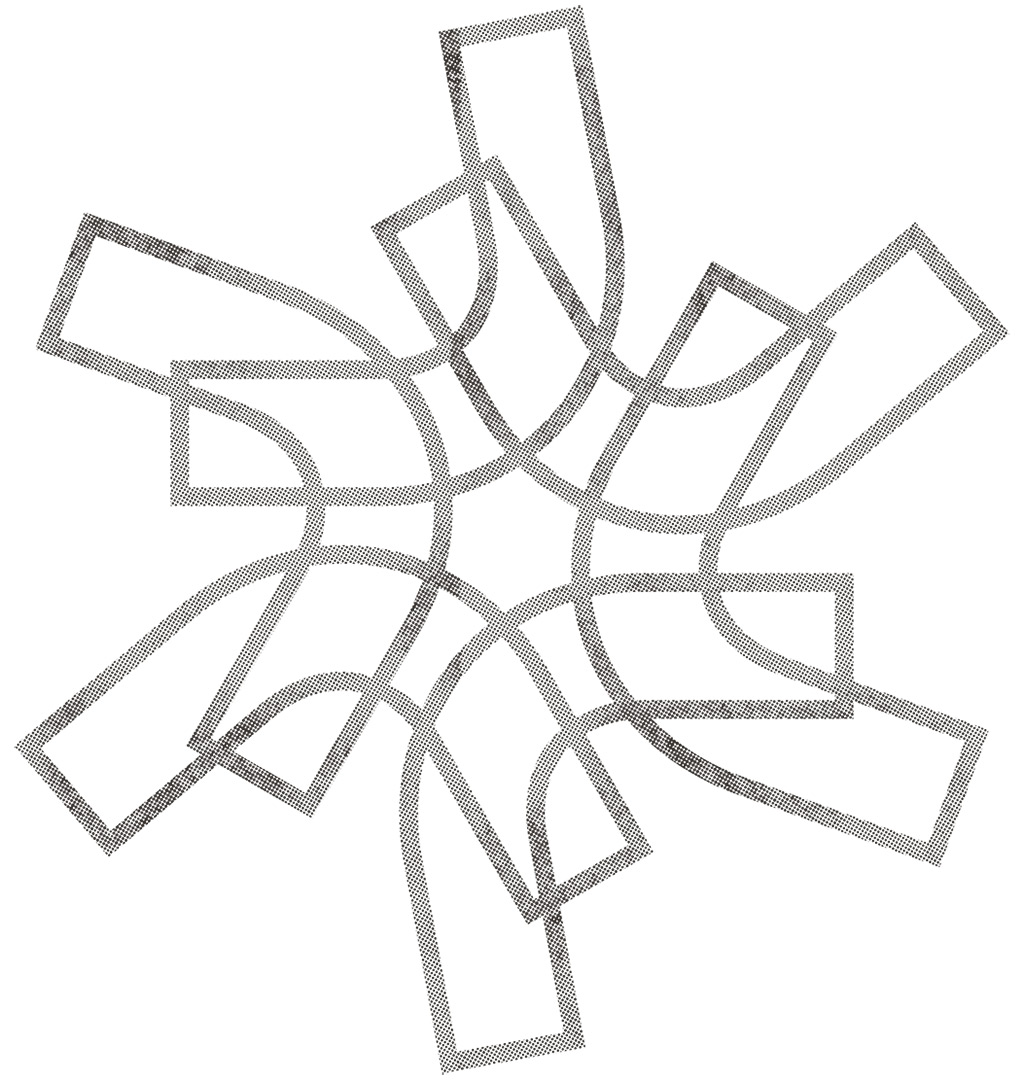

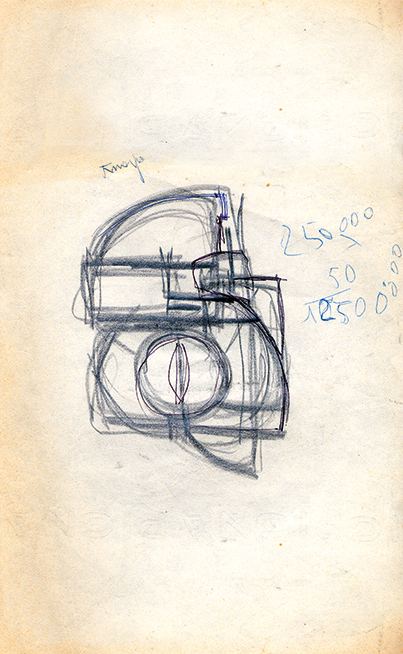

In the magnificent sketches which try and try again, which develop and refine a hook-like form (an incessant quest for that which would become a structural morphological concept), one can see the search for harmony and classic beauty, for well-made sculpture, which Cascella sought and found over the course of his artistic career. And perhaps, in all his planning and creativity, the familiar mould linked to his maternal grandfather remains. After all, his grandfather was a German mechanical engineer who moved to Italy to design combustion engines for Fiat, also drawn to processes which turned the coexistence of forms into the centre of thought and design.

The hook, a functional experience which soon would become the symbolic conceptualization of interlocking, was a recurrent theme after his participation in a 1958 competition to design a memorial at Auschwitz (which he won alongside architect Julio Lafuente, though it was never made), a key which became an authoritative cipher.

The small yet essential Legame (1962) is emblematic, his only sculpture created from two types of stone which maintain that sense of an embrace, of proximity in difference, of a gap which isn’t distance but relational identity, a trace which, although differently, is also found in Tutto Grigio (1968). Cascella’s sculpture shows the traces of his early days working with pottery, of that doughy, soft craft, both in relation to scale and size, and to the freedom to use different materials (including quartz and lapis lazuli with their inevitable references to jewellery). So, not just marble and other stones, but all materials are the bearers of language and meaning, and this confers intrinsic movement and expressive liberty onto the work. For these reasons, Cascella can be considered one of the last great Italian sculptors to look to the ideal of classical aesthetics and harmony as an essential reference, more precisely in his proportions and love of all that is ‘well-made,’ even when incorporated into abstract signs.

Cascella didn’t belong to any one movement or trend; instead, he felt the influence of cultural and artistic contexts. He belonged to a dynasty of artists and was part of a family with a long history as an intellectual coterie. In over a century, at least three generations have followed after grandfather Basilio, a painter from Abruzzo who is remembered for Il suono e il sonno, a painted triumph of seduction and physical carnality; and father Tommaso, who never abandoned Pescara, painting sunrises over the Adriatic Sea for his entire life; and Pietro, the brother with whom he tried out his hand at pottery. The family tree extends also to Marco, his son, a doctor whose microscopes have taught him about the genesis and the mystery of life and whose paintings have updated the example set by his great-grandfather Basilio and the connections of his father Andrea. Connections whose cultural epicentre can be found in the Andrea Cascella Archives in Milan, in the rooms of the historical studio at 8 Via della Ferrera, a research centre for the reconstruction of critical devices, a storeroom of moulds, plaster casts, and maquettes. And there are more than enough recognitions for a credible registry, arising from public and private collectors who have supported and promoted his work around the world.

The embrace of stone, shapes, and geometry is his defining sign, the yearning for dialogue and union, the exchange between surfaces and materials, the potential interlocking of differences, the quest for grace in hardness. In austere shapes and graceful proportions, modernity appears, inseparable from the search for connection.

From drawing to partisan memorials, from ceramics to sketches, the oeuvre of Andrea Cascella says much about the man and his painful yet powerful humanity, made of curves, corners, angles, brutality and interlocking forms. Made of human harmony: always laborious, and always to be attained.